HomeFeaturesWolfenstein: Youngblood

Wolfenstein: Youngblood’s impossible 80s setting makes you want to save the worldBig hair, don’t care

Big hair, don’t care

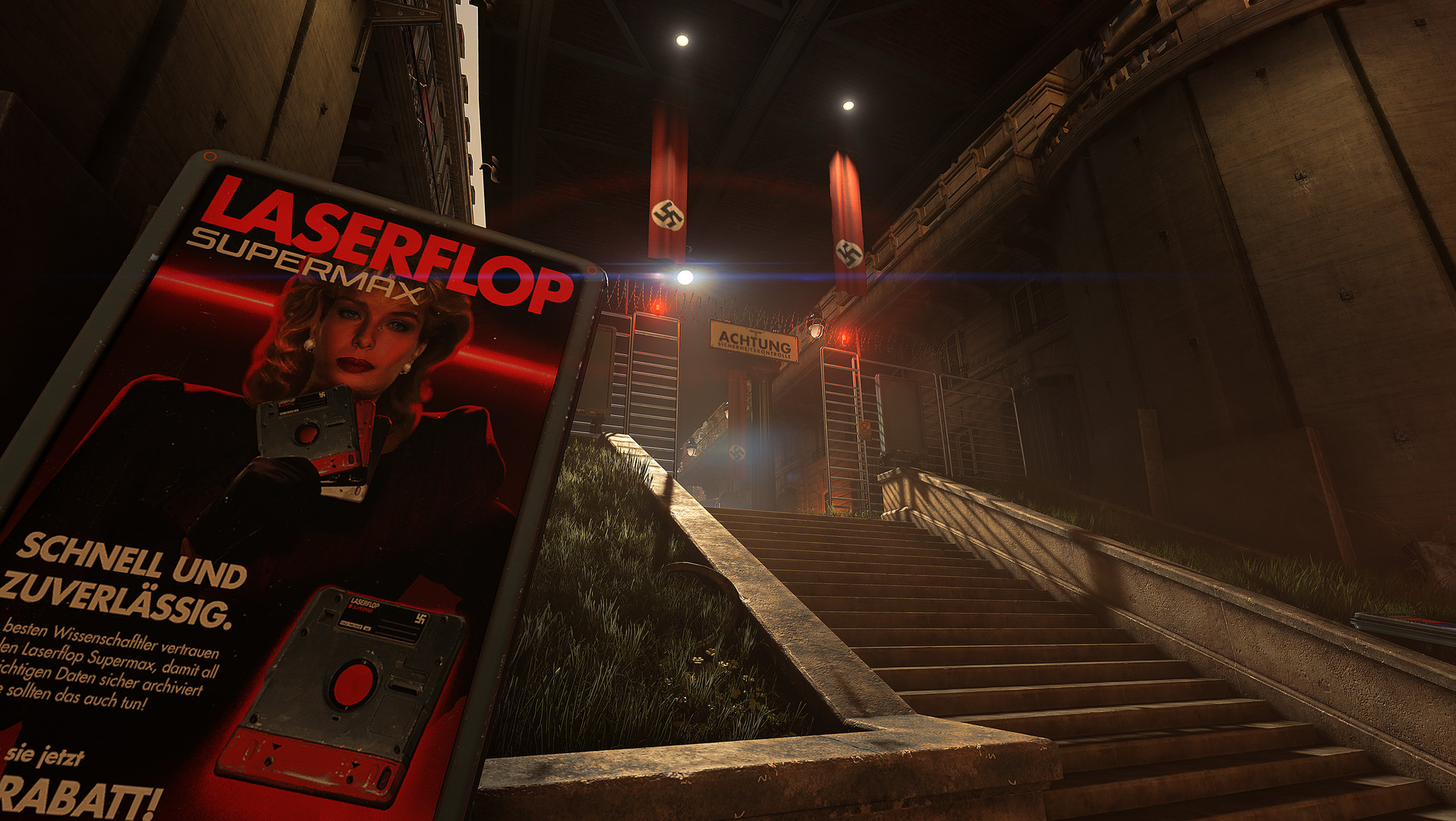

Alternate history first-person shooter (of Nazis, specifically)Wolfenstein: Youngbloodis a spin-off from the main Wolfenstein games. It’s set in 1980, and developers Machinegames don’t go halfway on it. The game is soaked with 1980s references, from early electronica and synthpop in the French Underground to 3D glasses and UVK Tapes (VHS tapes but, um, more Nazi-like). The in-game explanation is that Nazi dominance is so completethat it pervades popular culture.

Machinegames have taken this approach throughout their run with the revived Wolfenstein games. BJ Blazcowicz’s battles against the Nazis have been violent and fantastical but the Nazis of the games, like the Nazis of the real world, are more than a threat to BJ’s life: they seek to eradicate the world he knows and loves. In New Order and New Colossus this existential struggle is set in the 1960s, shifting from the nightmare of a firmly established Nazi postwar order to the sparks of American political and cultural resistance.

There is an implicit claim here: despite the horrors of a sustained Nazi success, an uninterrupted control of a city associated with the freedoms of romance and art, something has survived against the odds. Something innately good, familiar. But none of it should be possible. Nothing about the Nazi plans for a world-encompassing Third Reich left room for synth-heavy pop music. Their vision of a perfect cultural order centred onAryans in Lederhosen.

Watch on YouTube

Watch on YouTube

You run underneath the classic buildings, signage and balconies of Paris while evading the flamethrowers of Nazi supersoldiers. Above ground the totalitarian state rules all. Not just a historical totalitarian state either, but the one we have been visiting since The New Order, a postwar nightmare where Speer’s architectural visions became realised and the form of the Nazi state grew to fit ever more closely the function of continual, impenetrable oppression. The vibrancy of country’s identity, and of the 80s culture that we have a collective nostalgia for, has been pushed underground.

In his 1962 novel The Man In The High Castle, Philip K. Dick wrote of characters effectively lost in the nightmare of an alternate reality and teased with the possibilities of the existence of our own. Dick’s work has clearly influenced Machinegames since The New Order. In Youngblood Jess and Soph embark on a journey of transcendence, rising up into occupied territory and coming home to the welcoming sounds of freedom.

That freedom sounds like synthpop gives the player comforting reassurance the French Resistance has kept the spirit of a free postwar world alive. That perhaps, even given Machinegames’s implicit acceptance of the myriad imperfections of the postwar reality we have all inherited, the world and popular culture that rose from the ashes of the largest conflict in human history was, in a way, innately good. The Blazkowicz sisters are fighting to bring a tortured alternate history back to the correct timeline, albeit metaphorically. And the player wants them to succeed.