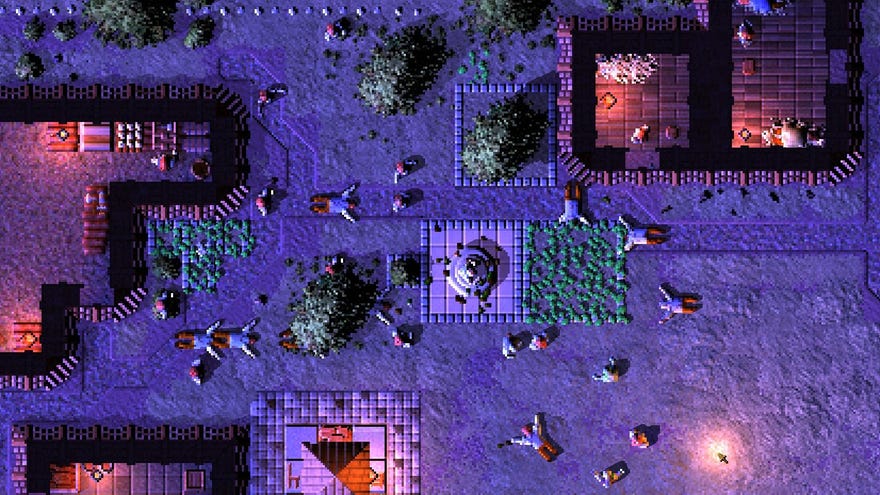

HomeFeaturesSongs Of Syx

It’s how you use it

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun, Gamatron

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun, Gamatron

The usual parts are there. Chop some trees, chip some stones, and chep some crops to get your pioneers' basic needs met, then get to expanding. But Syx isn’t interested in testing you or manufacturing drama. It’s not about surviving, not about building a happy little colony. It’s about how growth changes not just the scale, but the nature of a settlement. Despite similarities with its influences, it defines itself with a different dynamic, a whole different ethos to its peers. And it’s one that even playing it my own awkward way hasn’t broken.

Songs of Syx - TrailerWatch on YouTube

Songs of Syx - Trailer

A fair few building games start out too limited. Too often, the opening segments feel like a toll to be paid before the real game. Considering scale is a defining feature of Syx, you might think it’d be one of those. But the empire and city state phases are a culmination, not a baseline.

As is traditional, you start with a handful of colonists and a need to get more just so that everyone’s not juggling two or three jobs. But stability comes quickly thanks to the control you get over population. Your main source is immigration, but unlike Dwarf Fortress and its sudden invasions of 5-100 yoghurt weighers, prospective citizens queue up and wait to be let in, at the exact number and moment you decide. Syx is not combative, either. It’s about expansion and macromanagement, but you can get there at your own pace. The only direct pressure is raids.

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun, Gamatron

That threat can be prevented, too. The presence of a militia (refreshingly easy to train, and doesn’t prevent them from working) can be enough, with mine generally at a 5-8% chance of trouble per year even without iron weapons. Even when they target you, they practice sensible banditry, offering an ultimatum and time to meet it, and then must set out across the map, where they can be intercepted if you’re prepared.

But your ambitions can sit in the middle too. There’s no rush towards an endgame or ideal form. The intermediary stages are just as enjoyable, and you’re neither penalised for taking your time or forced into mass population, thanks to those immigration controls. For the sake of everyone’s sigh glands, let’s politely set aside any argument about any real world politics here, because its sheer function is transformative.

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun, GamatronImage credit:Rock Paper Shotgun, Gamatron

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun, Gamatron

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun, Gamatron

Colonists come from one of seven species. You get dwarf-ish Dondorians, insectoids who are mostly good for labour, a few rare ones that have to be found on the map and swayed or conquered. My favourite are the Tilapi, forest-loving herders whose culture demands a little cannibalism, as a treat. Despite being clearly based on DF’s elves (elves being the worst in all fantasy), they feel like a distinct thing, probably because everyone’s day to day lives are so mundane and relatable. Each species gets along a little better with some than others, but it’s not a flat bonus or penalty to relations; each has dozens of preferences and dislikes for particular jobs, public services, materials, and even shapes of building. Species with some animosity can get along fine if they all feel provided for and nothing too objectionable happens. You can set government policies on a per-species basis too, to placate a disgruntled demographic, or butter up the population who you want to see more of (happier residents spur more immigration from their kinfolk).

All this has conceptual consequences. Syx’s less antagonistic attitude produces goals beyond survival and stability, to really defining and leading your settlement. Individuals don’t really matter despite each getting a name and description, which is a good thing considering how quickly they’d become irrelevant. But they matter collectively. You can absolutely have a monoculture town, excluding specific people or even enslaving or genociding them. Each culture has its own attitude to freeing slaves, who don’thaveto be racially targeted. Enslavement can be reserved for war captives or specific crimes instead (which interestingly, in a dark fashion, makes it possible to deprive a people, frustrating and provoking them into crime, creating a conveniently neoliberal-deniable form of racial slavery), or rejected entirely; this isn’t an edgy game at all.

Image credit:Rock Paper Shotgun, Gamatron

Syx isn’t specifically about how settlements reflect and generate ideology, history and culture. Its focus is somewhat mechanical even if you don’t build a city as a huge and efficient machine. But even with its store page showing neatly organised grids and carefully measured geometries, it’s about growing a society. While Dwarf Fortress is about “stories”, they’re often individual dramas, and its unofficial “losing is fun” motto reveals that those stories are aboutdecline. The buildup of a typical fort is there to preface the story of its destruction.

Syx is about the growth. Its process, its shape, and how its population and focus and philosophies shift (or refuse to) from what you set out with. That growth feels natural, not a capitalistic delusion of inifinite expansion or mathematical videogame notion of Make Number Go Up; there’s even inflation, which instead of changing prices directly trickles money away over time, encouraging you tospendit, while degradation presses you to sell. Resources are to be used, not hoarded. Using them makes people happier, encouraging more to join, both producing and consuming more, changing the town a little more and restarting the cycle. Instead of doing the same things but with bigger modifiers, it’s rather likeDistant Worlds 2, shifting focus and playstyle as you grow from planet to empire, from burg to barony.

Songs Of Syx is a marvel. It delivers the satisfaction of running an effective machine, and the warmth of a living place. It offers escalation and shifting ambitions without wrenching away the parts you were enjoying. A Dwarf Fortress level of control with a The Settlers pressure level, letting you relax and watch your people take care of things without constant intervention. It’s an incredibly PC game that feels like a lost treasure of the Amiga, and despite the many more parallels I could draw, feels entirely different to just about everything.