HomeFeatures

I Am Dead is a puzzle game about a ghost who can look inside fruitHe’s going through a lot right now

He’s going through a lot right now

“If you’re a ghost, and you walk through a wall…” asks Richard Hogg, in the tone of a man confronted with a real head-scratcher, “…do you get to see the inside of the wall?”

It’s a good question. The kind which, for most people, might fuel a good half hour in a pub, or a 2am chat with a partner who can’t sleep. But for Hogg and his long-term collaborator Ricky Haggett - who last year spun a thought aboutthe simple pleasure of stacking shelvesinto the phenomenalWilmot’s Warehouse- it’s a question worth writing a game about. That game isI Am Dead, and after watching Hogg and Haggett play for half an hour, it looks like exactly the tonic I need in the middle of this long, dark year.

Everything inI Am Deadhas an inside. Which shouldn’t feel so weird, considering that’s how physical objects tend to work. But in games, we’re used to all things being hollow: big parcels of nothing, wrapped in the thinnest integument of texture, in an illusion that the smallest clipping error can shatter. So even though I Am Dead’s world is bulbous and colourful, following the visual grammar of Hogg and Haggett’s distinctive cartooning style, it has actual weight. It feels bizarrely, intrinsically solid.

But how can Morris do that, when the living can’t see him, and he can’t interact with their world? Well, he might not be able to, but there’s potentially someone who can. That someone is Ogden Beckett, also dead, and something of a local legend in Shelmerston. Everyone in the town has a story about this larger-than-life character, and Sparky reckons that if Morris can work out from these stories where they might be able to track down some mementos from Ogden’s life, she can train her ghostlyJacobson’s organon his existential scent, and track him down to seek his help.

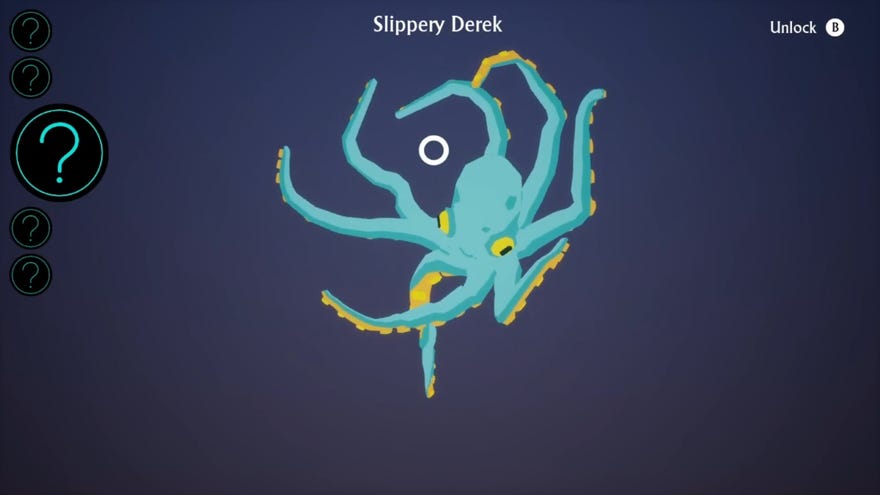

There are other things to do, of course. Virtually everything in every environment is worth investigating for its whimsical secrets, and there are also some splendid sidequests. These present you with abstract 2D images, which are cross sections of objects somewhere in the world. Should you find the right transect for the right object, you will discover grenkins. Grenkins are a kind of pleasant spectral vermin, and each one is unique. They are pure Hogg/Haggett doodling joy, and despite loathing collectibles in most circumstances, I want to find them all.

All in all, I Am Dead feels like a much more personal bit of work than Wilmot was. Both Hogg and Haggett have experience of seaside towns of the kind Shelmerston archetypes, and I spot many of their interests tucked into the edges of the game. At one point, we look inside a vacuum cleaner and see a little tin Buddha, and Hogg pipes up. “That’s based on a real thing that happened to me. I accidentally hoovered up a little tin Buddha, and I had to cut the hoover open to retrieve it.”

Colourful tetrahedrons then appear in the Buddha’s head as we look through it, forming a weird, scintillating pattern, and Haggett reflects on how nice it looks. “There’s all this lovely animation that just comes out of slicing 3D geometry,” he says, “in a way we couldn’t predict until we made it and sliced through it.”

“The tetrahedrons represent enlightenment,” Hogg deadpans.

It’s worth noting that this game is also very funny, in a way that really appeals to my sense of humour in particular. At one point, we found a burly construction worker, imprisoned in a weird concrete bollard thing “for being rowdy”, and I laughed out loud. There are also fish people, who when I see them, are queuing up for toast. “They used to live in the sea caves,” explains Haggett, “but now they’re here on the surface more often. And they’re obsessed with dry food. Admittedly, that was mainly an excuse to put loads of toasters in the game, though, ‘cos they’re great to look inside”. We look in the toasters; I can see what he means.

These are not pretentious men. And yet still, I can tell that I Am Dead has some big, but quiet, things to say about death and change and memories. Morris loves Shelmerston, and he wants to stick around there, but according to Haggett, he can see that it’s changing in ways he’s not at ease with. I’ve got a horrible feeling that Morris’s story will lead him to the realisation that it’s time to move on, and I can’t help myself. I ask if it’s got a happy ending.

“It does,” says Haggett, at the same moment as Hogg says “does it?”, in the same tone as Thor saying “is he though?”. “There’s a lot of sad stories along the way,” concedes Haggett, after a moment. “It’s bittersweet.”

I suspect it’s going to make me utterly fucking sob. There’s nothing morbid or hammy or overly sentimental about I Am Dead, but I could almostsmellthe sadness, in the way you can smell when it’s about to rain. I know that in this case, the rain will be coming out of my face.

I Am Dead is “nearly done”, apparently, and out very soon, though theSteam store pagewon’t be pinned down past a broad 2020 release window.