HomeFeaturesCrusader Kings III

Hands-on preview: Crusader Kings 3 is the RPG that will suck you into grand strategyGadzooks etc.

Gadzooks etc.

Crusader Kings 3is coming on September 1st, and after having access to an early build for a few days, I’m seriously impatient to get back to scheming, disinheriting, and declaring myself the new pope. It’s got that terrible magic that leads to all-day-and-half-the-night sessions, and that’s largely because, secretly, it’s two games at once. It’s a strategy game, obviously. But it’s also a roleplaying game, and a really good one at that. So was 2012’sCrusader Kings 2, of course. But developers Paradox have been shrewd in identifying what made that weird hybrid work as it evolved through fifteen expansions, and have put it front and centre in CK3 from day one.

In CK3, the start points are either 867AD or 1066AD, and you can play as anyone who ruled any sort of political entity across all of Europe, plus big chunks of Asia and Africa.

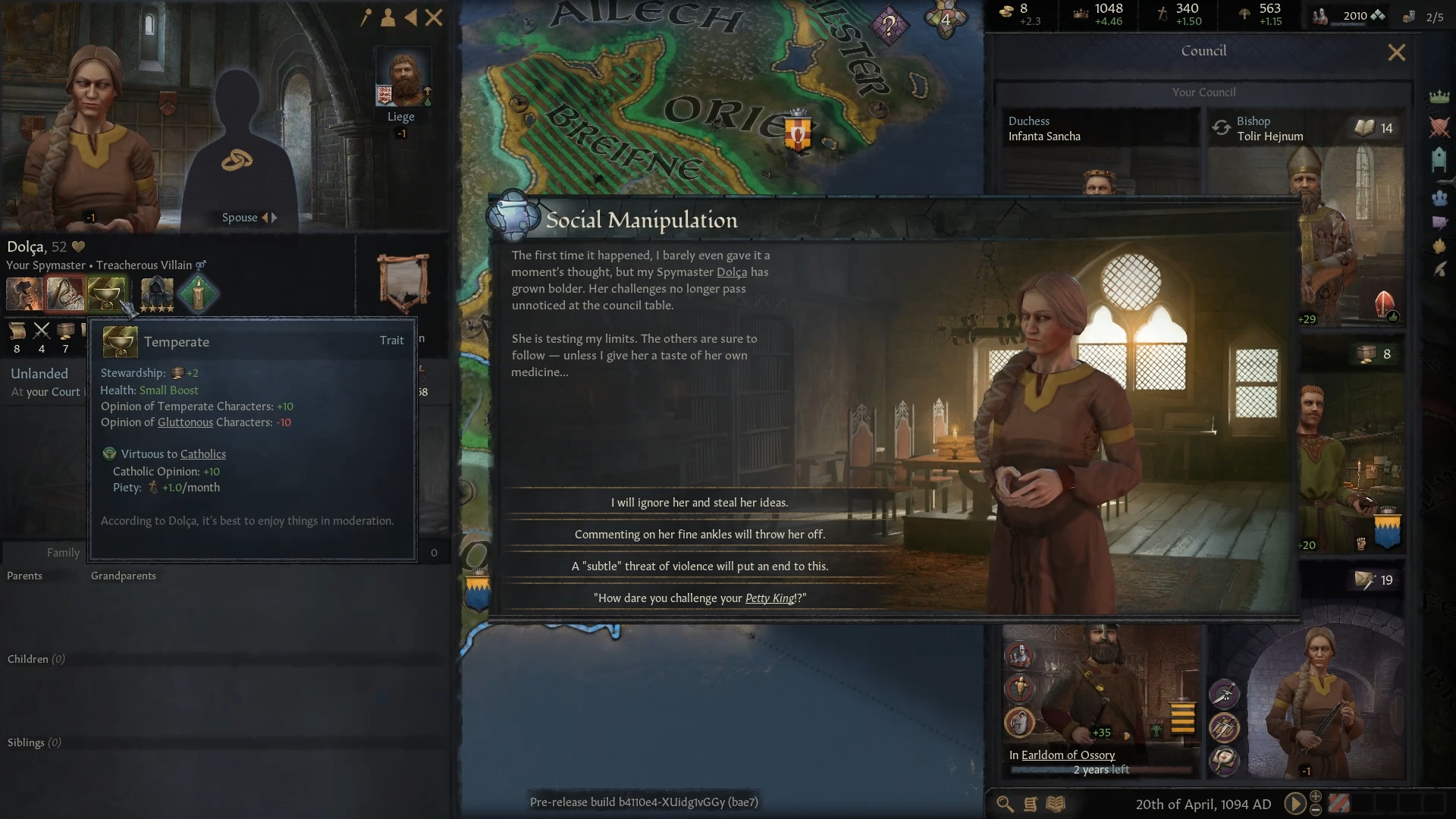

In brief, it’s a game where you control the successive inheritors of a medieval dynasty from the Early Middle Ages, through several hundred years of wars, religious schisms and backroom stabbings, until the world can’t reasonably be described as medieval any more. You view that world via a sprawling, top-down map, where you’ll have lands to manage, cities and strongholds to build, wars to fight, and diplomatic relations - with powers both foreign and internal - to handle. There’s a fair bit of clicking on the map to build farms, move armies and the like. But the really juicy elements of play take place through portraits: 3D pictures of kings and that, attached to a whole raft of statistics, traits and simulated genetics, and pokeable via drop down action menus.

Rip in peace.

CK3 does a much better job than CK2 of making your long-term dynastic play feel meaningful and rewarding. Your actions in life build up your various traits as ruler, such as piety and prestige, for example, which determine what opportunities come your way and how you can react to them. But some actions also build the reputation of your bloodline, and can have repercussions for hundreds of years. If you’ve been blessed with a surfeit of children, let’s say, it’s well worth marrying them off to distant empires, since even though there might be little in it for you in the short term, it’ll mean spreading your name and your DNA across the world. This develops your dynasty’s reputation (which, like everything in a Paradox game, is tracked with a tidy little number that changes slowly over time according to a swarm of fractional modifiers), and as it rises, all sorts of little bonuses will start nudging at the edges of the things you do. Gain Kardashianesque levels of familial fame, and you’ll start unlocking persistent perks that benefit all your descendants, from increased martial ability through to longer life, better chances of inheriting positive genetic traits, and beingliterally dreadful.

It always pays to think a generation ahead. Since every character has a modelled personality of their own, which develops as they grow up, you can spot the real maniacs in line for the throne early, and find creative new ways to deal with them. Put them at the head of an army headed towards certain death… then panic as they become a revered war hero after a surprise victory. Disinherit them… then die in a toilet stabbing when you forget their best friend is the spymaster. Lumber them with a matrilineal union to the unlovable scion of some dump on the rough side of Norway… then watch as everything falls apart in a frenzy of claim-pressing from the fjords, when you you die from a burst face after botched eye surgery, conducted on the advice of a physician you forgot was a halfwit.

Always a great idea to get in a protracted feud with the person in charge of protecting you from assassination plots.

As you can imagine, there’s limited worth in having too concrete a masterplan. In heir management, as with so many other areas of the game, every decision you make spreads its causal tendrils to a dozen other quietly tracked little variables, and while most of the effects are transparent enough, you can’t have that many butterflies flapping all the time, and not expect to cop a few hurricanes. Soon, you come to accept that even the most stable period can come crashing down around your royal ears with just a few misjudged calls, and you come to relish the improvisation and adaptation that comes with a sudden death.

Just thinking Christian stuff, y’know.

Mans at arm.

Of course, the problem with having all these teeming, interlinked systems is how to make sense of it all, especially for new players. CK2 was notoriously opaque to many unfamiliar with the wider genre, and could be a headache even for veterans, with important actions and information tucked away in unexplained places, and a wealth of succession law and feudal dynamics to comprehend in order to have any idea what belonged to who. CK3 makes an impressive effort to rationalise things, with a UI redesigned pretty much from the ground up, an in-game encyclopaedia, and an absolute onslaught of tooltips in every line of text. Plus, the tutorial genuinely teaches you the game this time, which is nice.

All in all, the information you need to understand something is rarely more than a click away, and the UI is constructed to help you avoid missing out on interesting options available to you. Most notably, an “advice” button at the top, should you enable it, keeps track of what wars you can start, which vassals are miserable with you, and other things you could use reminders of. Oh, and I like the new building system, too. I’ve never really enjoyed building or development in Paradox’s historical games much, but either through redesign or just presentation, I found castle-building and the like a lot more interesting in CK3.

Further to that, there are a couple of universal issues. For all that it’s been improved, combat is still a bloody quick way to completely undo hours of work with one error, and while it’s not a design flaw, it can still feel anticlimactic at times. Expansion wars, even when successful, are often a job that needs to be done rather than a treat. Succession, titles, and territory also remain confusing, despite the game’s very best efforts at spelling out how the feudal system works. I’m happy to accept that I’m just a bit thick when it comes to abstract legal concepts, and maybe that’s all that’s keeping me puzzled when trying to work out what titles will pass where after a ruler’s death. But still, that whole side of the game is just a mass of similar-looking heraldic shields to me, and I often decided just to shrug and accept the consequences, rather than spend too long trying to figure it out.

But that’s where CK3’s dual nature shines. Because in the moments where it does dance beyond the reach of comprehension as a strategy game, it’s still absolutely solid as an RPG. The character game is so intriguing, you find yourself taking a robustly “so be it” sort of attitude, throwing yourself into situations that might well be disasters, simply because they’redefinitelywhat your character would do. Interesting responses lead to more interesting choices, and actions become their own reward, as opposed to tools to be deployed drily in pursuit of a slightly wider kingdom. And that, I think, is why CK3 stands a good chance of being a hit with newcomers, without alienating fans of its predecessor. While it doesn’t tame the complexity at its heart, it certainly makes it a lot easier to stay in the saddle.

Caveat: Paradox have asked that I remind you that the game as pictured is still in development, and all visuals are subject to change.