HomeReviewsGhostWire: Tokyo

You’ve been Tangoed

A Walk In The Rain In Ghostwire: TokyoWatch on YouTube

A Walk In The Rain In Ghostwire: Tokyo

After the unrelenting anxiety of The Evil Within, this is certainly a more chilled time. It’s not remotely scary, for one. Its cast of backflipping highschoolers and umbrella-wielding salarymen have more in common with cartoonish spirits of Luigi’s Mansion than the J-horror abominations of Tango’s earlier game. Okay, I winced the first time a scissor-waving giantess (big Lady Dimitrescu energy) snipped out my soul and stripped my combat abilities, but even she’s easily robbed of her power with a paralysis trap and a rocket to the face. The whole thing carries the air of giggling kids sharing sleepover spook stories than anything seriously traumatising.

Not that you’d see it playing on regular difficulty, which is generously tailored for exploration and hassle-free fights. I’d say to the point that combat becomes shapeless, a simple target gallery where ghosts crumple after a few wind bullets to the chest. Hard difficulty is where Ghostwire’s clutch finds the bite and its systems make sense. Elements like stealth takedowns and a bow that lets you thin a crowd before a fight, or floor-based traps that can stun, distract or leave a phantom susceptible to a heart-ripping takedown. Without that slight hint of desperation, these are just unneeded lumps bobbing in a soup of repetition.

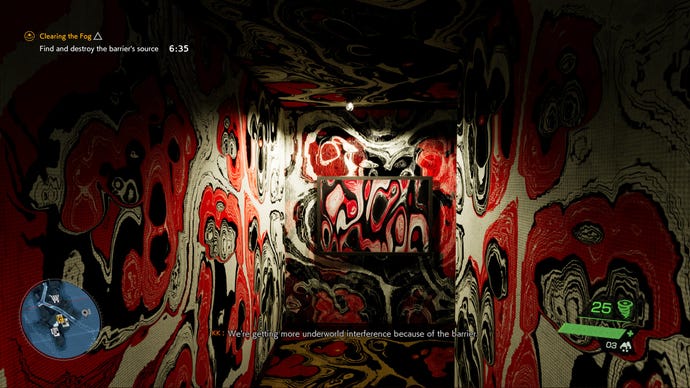

Given the desire to step away from the studio’s previous work, it’s ironic that some of the best sequences involve hallucinatory, impossible internal spaces that could have been lifted wholesale from The Evil Within’s trippier playbook. Several setpieces see you racing to escape from apartments that fold in on themselves all Inception-like, or explore corridors as swarms of jittering plastic chairs block your path or nightmarish images paint the wall. Much of it has the energy of a nonsensical student film, but the flip-flopping of reality makes for a striking artistic and technical showcase.

Overuse of regular enemies is noticeable in side quests. You’ll meet spirits who can’t move on until you’ve investigated an apocryphal local legend: a trash vortex, the apartment block lift with one floor button too many, or a studio head who won’t stop playing Beethoven. The setups wrap basic ‘go here, do this’ tasks in stories that, according to review notes, are lifted from the developers’ lives: what creepy fun! But that most tales end fighting common fodder robs them of that drama. The dark pull that lures people to a suicide hotspot in a tenement building? It’s another dude with an umbrella. Just like that, creepypasta becomes limp, overcooked penne.

Map filler is equally disappointing; the sure sign of a team not really knowing what to do with the open world they’ve built. Like the side quests with their urban legends, the game puts a folklore skin on drudgery: you’re chasing sickle-handed dust devils through forests, you’re chasing long-necked Rokurokkubi down alleys, you’re chasing living cloth Ittan-momen across rooftops… you’re chasing a lot of things, basically. Strip away the art design and it’s no more engaging than pursuing endless wind-swept papers inAssassin’s Creed. Arguably, it’s worse here, as Ghostwire’s versions are bizarrely easy. Many last for all of ten seconds; barely a distraction.

Then there’s harvesting souls of Tokyo’s vanished population: hundreds upon hundreds of blue clouds crammed down alleys and sprinkled on rooftops. Collecting these constituted the meat of my playtime, as they are needed to both level up and unlock the true ending of the game (full disclosure: I called it a day at 182,000 of 240,000 collected). I likened it to Crackdown’s orb hunt in mypreview, and I think that’s apt: one cluster inevitably puts you near another, and the next thing you know you’ve lost an hour to tidying up. It’s a good podcast game - why not tryEWSas you mindlessly tick off trinkets? - but lacks the complex traversal to be more than that. Outside of a longer glide and a late ability to grapple to any rooftop (gutting whatever aerial navigation challenge existed) it just plods ever on.

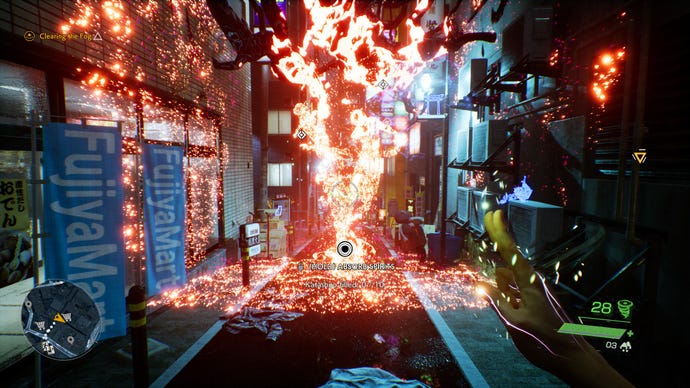

Picking over the nooks and crannies does make you drink in Ghostwire’s one truly standout element: the city itself. As mentioned in my earlier hands-on, this is a neat bit of first-person tourism; it opens with a gorgeous rendition of Shibuya’s traffic crossing before pulling you into a warren of shouty shop fronts and up a towering spire that riffs on Shibuya Sky (for trademark reasons, I’d imagine, few places use real-world names). If your setup can handleray tracingthis is especially pretty; Tokyo’s wall-to-wall billboards turn a sea of puddles into a rainbow extravaganza. But even without it, the artificial luminance of the city, and combat’s focus on elemental whooshes and leashes made of sizzling light, make this a flashy world to behold.

But it’s actually when the game leaves the more iconic landmarks that it got under my skin, pushing into suburbs and forgotten social projects, far from the tourist traps. Yes, it helps that everyone has vanished, but even so, the fringes of the map carry more of a supernatural throb to them - especially the disquieting, looming apartment complexes built to accommodate the post-war urban boom. Here, in these uniform blocks, marked with stark lettering and soundtracked with the cawing of birds, the game finally finds the chilling effect that can’t quite take root in busier areas. It’s a side of Tokyo I’ve not seen in much pop culture and feels like something that only a team fully embedded in the city’s history would tap into.

In a roundabout way, this is a mission success for hands-off Mikami - Ghostwire certainly doesn’t feel like something he’s made. It’s too baggy, too loose, lacking the powerhouse momentum I associate with his previous work. What’s here just never clicks fully into place: a beautiful setting, tactile combat, tantalising hints of the beyond, but not enough to populate a city this big, leaving stodge to fill the vacuum. Mikami’s tinkling ivories aside, Ghostwire is a tad too discordant.