HomeFeatures

Game design as a Harvesting: the implications of Amnesia’s most horrible idea"Only with careful performance will the victim yield maximum effect."

“Only with careful performance will the victim yield maximum effect.”

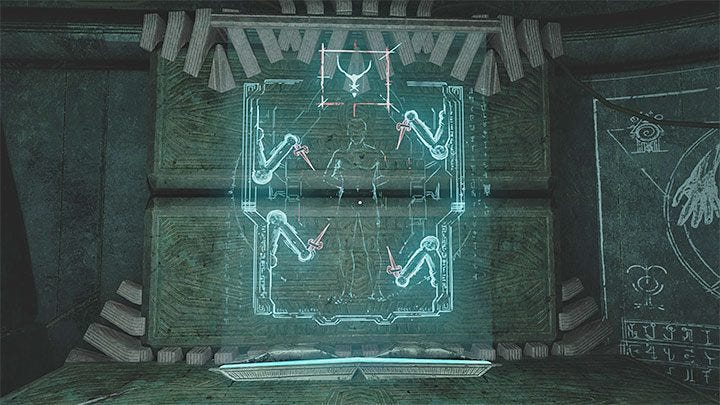

Image credit:GamePressure/Frictional

Image credit:GamePressure/Frictional

The most ghoulish of Amnesia’s many ghoulish ideas is “vitae”. It’s a luminous, blue-green fluid that can be used as an energy source, a chemical catalyst and a supernatural healing agent. Each Amnesia game is broadly a story about the production of vitae, with some levels consisting of huge distillation and refining apparata, and major plot developments tied to what you do with it. In the originalAmnesia: The Dark Descent, you’ll brew potions using vitae in order to keep a decapitated head alive. In 2020’sAmnesia: Rebirth, you’ll use ornate metal cannisters of the stuff like batteries to power otherworldly machines. Vitae is the blood and breath of Amnesia, the grease upon the narrative axels, the fuel in its boiler, the miracle McGuffin that sustains its nastier flights of fantasy. But whatisvitae, exactly? Agony.

Vitae is a psychosomatic substance extracted from the bodies of tortured beings, and especially, human beings. As Alexander, the antagonist of The Dark Descent, explains in one of the game’s grimmer found documents, it’s generated in response to pain and fear, like the so-called ‘stress hormone’ cortisol. “As long as the body suffers it will continue to produce the vitae and saturate the blood with its properties,” Alexander writes. Obtaining vitae from a person isn’t, however, just a question of brutalising them relentlessly: it takes subtlety. Craft. “Only with careful performance will the victim yield maximum effect.”

Top 12 Best Horror Games to Play on PCWatch on YouTube

Top 12 Best Horror Games to Play on PC

Image credit:Frictional Games

“The way most animals kill other animals is not kind,” Grip goes on. “We humans think we’re gonna kill the animal in a humane way, but a lion in the savannah doesn’t try to kill something as quickly as possible. Fatally wounding is okay, as long as I don’t lose track of it. It takes two hours to die - I can wait, that’s no problem. So you’re optimising. And for humans that comes in at the society level, with factories and so on. The lion is okay with the gazelle bleeding out, and the factory owner is okay with their workers suffering, because this is optimising my labour force.”

The idea of inflicting “a certain amount of suffering” in the name of optimisation could also be a manifesto for horror game design. The Amnesia games often invite comparisons between Alexander’s “careful performance” of vitae extraction and the way they themselves are laid out and paced to stimulate dread and terror. They may not harvest your vitae, but as products, they must operate upon the player in similar ways, and often seem to delight in advertising this.

Is this deliberate self-commentary, I ask Grip? “Not deliberate, but we noticed how similar it was already in The Dark Descent when Alexander goes over his methods,” he says. “It is quite interesting how close torture and making good horror ‘entertainment’ are. While I do not see our games as a metaphor for this, it is a very interesting subject.”

Image credit:Frictional Games

There are also equivalents in Amnesia’s design for the concept of pacing the onslaught and “resetting” the victims of vitae extraction. Like many works of horror, the games offer moments of calm and security to vent some tension and ready you for the next gauntlet of scares - well-lit siderooms that replenish your character’s sanity in The Dark Descent, flashbacks to relatively innocent times in Rebirth, or the administration chamber ofAmnesia: The Bunker, with its inexhaustible oil lamp and reassuring metal doors. These safe areas are a form of anaesthesia, cleansing and refreshing the nerves, and the games sometimes play up the association with their own, represented methods of pacification. In The Chinese Room’s Amnesia: A Machine For Pigs, there’s a barracks where you’re permitted to wander and spy on the titular abbatoir’s pitiful, vivisected workforce in safety, all the while listening to the same classical music that, as you learn elsewhere, “calms the product” during its journey along the pigline.

It’s especially unpleasant to reflect that these calculated reprieves might include each game’s opportunities for empathy. Most Amnesia games offer some kind of branching “trolley problem” for the player, with the opportunity to help or harm some helpless NPC - a moment of kindness you must weigh against the cartoonishly awful things your character did, before losing their memories and relinquishing control to the player.

Image credit:Frictional Games

“Vitae” production might take inspiration from the alchemist at their crucible, but Amnesia’s self-referential game design offers a pretext for comparison with more recent forms of “energy extraction”. In particular, I want to read vitae as a metaphor for another kind of distilled “lifeforce”, digital data. Even before you consider the uses and abuses to which it may be put, data has become an inherently dehumanising and obfuscatory concept. As advocacy group Defend Digital Me argues ina paper calling for “sustainable” data policies, it’s commonly figured as a necrotic fluid akin to a fossil fuel, a valuable but volatile compound that can be drawn off and converted, and which “leaks” from the human body when it is obliged to exist in a predatory surveillance environment.

Image credit:Frictional Games/Bit-Tech

This frenzy of optimisation and efficiency recalls Upton Sinclair’s account in his novel The Jungle of how 19th century slaughterhouses “use everything of the pig except the squeal”. But it also captures the exhaustive scope and granularity of modern data-gathering services, with networked videogames especiallyequipped (if not necessarily permitted) to track everythingfrom how quickly you level-up to your usage of possible slurs in voicechat through changing facial expressions and the electrochemistry of a playtester’s sweat.

A Machine For Pigs is also the ultimate incarnation of Amnesia’s exploration of the overlap between torturous energy extraction and horror game design. Here, the vaunted “critical path” has become a slaughtering line: to reach the game’s end you must repeat the journey of a carcass through the abbattoir, with story beats that might as well be labelled dehoofers, scalders and eviscerators. But the game also portrays this journey as one of self-recovery, with protagonist Oswald confronting his doppelgänger and embracing a second life as a saboteur. While framed in lurid Penny Dreadful style, this theme transcends Amnesia’s grotty fiction and suggests a routine, but far from empty course of revolutionary action: become intimate with the mechanisms of harvesting, whatever form they may take, so as to disentangle ourselves from them and dismantle them from the inside.